At the bedside, tempo is not a musical decision, it’s a vital sign.

As Certified Therapeutic Musicians, we enter spaces of heightened vulnerability. Breath is often labored, irregular, or suspended between life and death. In these moments, breath becomes the most honest communicator of a person’s inner world.

And it’s from that breath, perhaps strained, shallow, or whisper-thin, that we draw the pulse for our music.

Why Breath? Why Tempo?

Breath is the thread that ties consciousness to physiology. In the dying, it’s often the last autonomous function to remain. In the anxious, it’s the first to change. It’s the body’s metronome, and unlike the mechanical click of a BPM counter, it’s changing, adaptive, alive, responsive.

Breath is not just a metaphor for connection, it is connection. It’s a function we can consciously influence that also runs involuntarily. This dual nature makes it a gateway between self and other, between control and surrender, between sound and silence.

When we talk about using breath as tempo, we aren’t talking about mimicking rhythm. We’re talking about entering into relationship with the patient’s autonomic nervous system. This is entrainment.

Our harp strings become a translation of their internal state, not to match it, but to meet it and offer an invitation.

Tempo as Nervous System Dialogue

Let’s break down different types of breathing:

A rapid, shallow breath suggests sympathetic activation: fear, pain, anxiety. Music played at too slow a tempo here may feel unmoored, even dissonant to the body’s current reality. Instead, begin with the breath. We can establish safety by synchronizing, not too precisely, but enough to say, “I see you. I’m with you.” Then gently slow, elongate phrases, and allow the breath to follow.

A deep, slow breath, or even breath-holding, signals parasympathetic activation, which reflects calm, rest, or deep relaxation. In this state, music that is too dynamic or changeable can feel intrusive, disrupting the tranquility of the moment. The appropriate tempo might involve long, sustained tones, minimal harmonic movement, and phrasing that honors stillness.

Apnea or Cheyne-Stokes breathing (often present at end of life) introduces irregular cycles of breath and pause. This is where true presence is required. Don’t try to force a rhythm here. Let your own breath guide you, not to structure the music, but to keep you anchored.

When the breath returns, so does the phrase.

Practical Ideas for CTMs:

Breath-Mirroring Warmup

Before playing, try sitting quietly by the patient, observing their breath. Let your own breath begin to mirror theirs, not to change it, but to understand it. This is not passive observation, it’s active listening.

Phrase Length = Breath Length

If the patient’s breath cycle is 8 seconds, try shaping a phrase that breathes over 8 seconds. Include rests. Think of each phrase as a wave: rising, cresting, receding.

Pulse Without Meter

Avoid strict rhythmic structures unless they’re clearly helpful. Instead of counting time, try feeling time through breath. Let one note hold until your own breath tells you to release. Let resonance trail like an exhale.

Harmonize With Internal Tempo

Some CTMs use pulse-based improvisation: choosing a central tone and improvising around it, allowing the space between notes to expand or contract depending on the moment. This makes your tempo organic, not imposed or forced.

Play the Silence

Sometimes, the most powerful entrainment is in the pauses. A well-placed pause, listening to the gradual decay of the resonance of the sustained notes, gives the patient permission to rest, to breathe fully, or to let go.

Painting Entrainment: My Series in Breath and Color

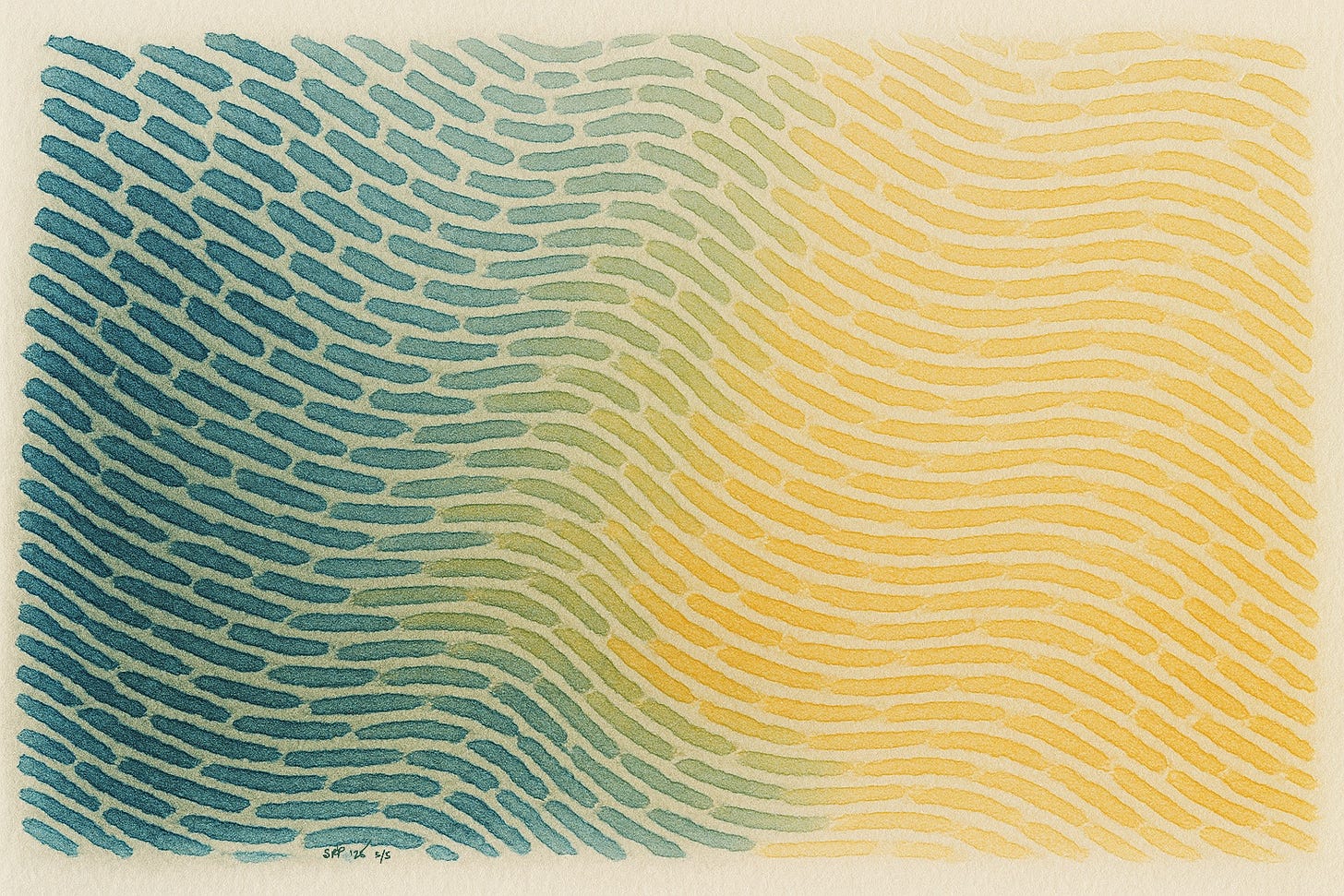

To illustrate this essay, I created a group of watercolor pieces in an attempt to describe this breath-based entrainment. The final inspiration came from our visit to the Van Gogh exhibit at the MFA Boston last week, where I spent some time visiting the Roulin Family Portraits exhibit. These moved me, not for their vivid colors, but for the way Van Gogh used patterned texture and the ways he suggested presence to describe scenes.

In Enclosed Field with Ploughman, VanGogh layers gently curving strokes that draw the eye across the landscape. These forms aren’t rhythmic in a musical sense, but they invite a slow, attentive gaze, like following the arc of breath. I translated this into watercolor by shaping curved strokes that broaden, soften, and taper, mirroring the expansion and release of breath over time.

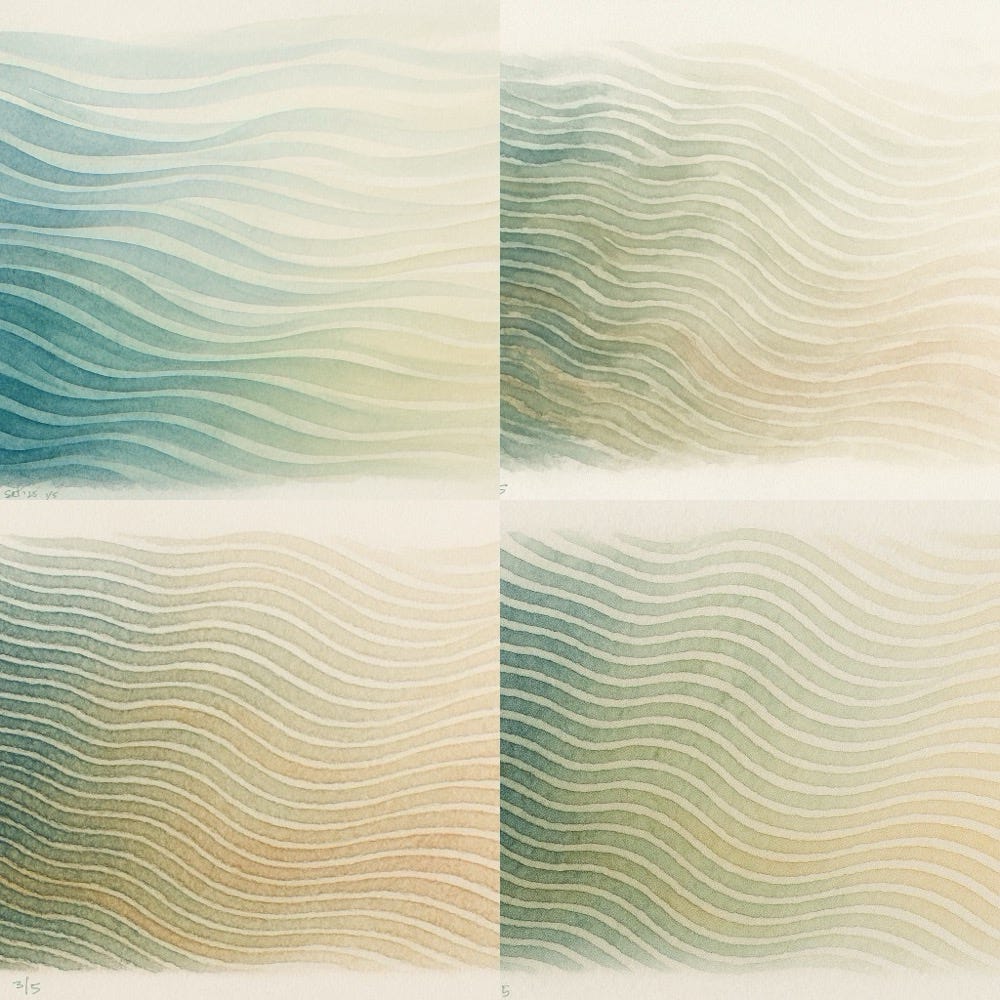

My compositions flow horizontally in layers, like atmosphere or time passing over a patient’s bed. Rather than completing a single image, I approached these as a series of five, each building on the last, a visual meditation on the therapeutic process of entrainment.

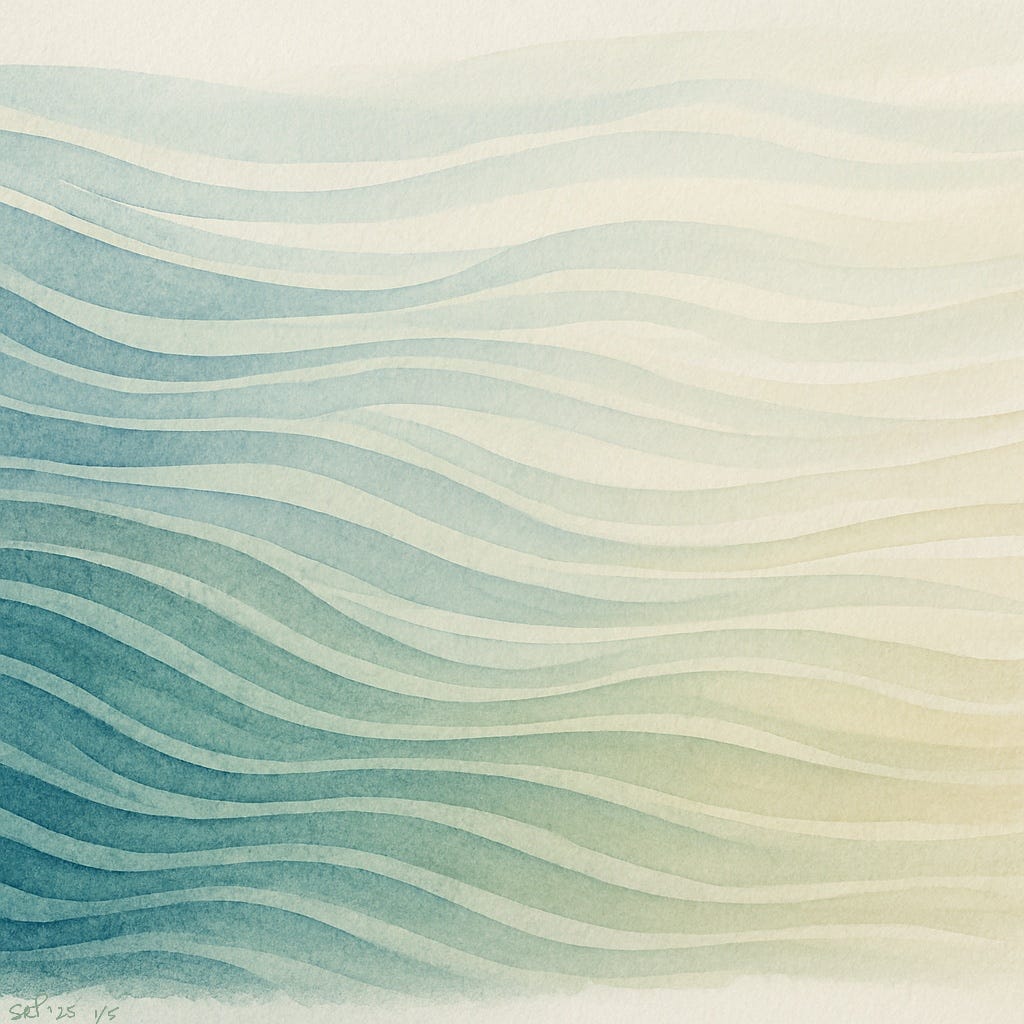

The first painting begins in atmosphere: a loose wash of movement, gentle arcs, and ambient flow, created on my iPad in Procreate. There is breath here, but it doesn’t feel personal to me yet. Like the moment before contact, to me it ends up reflecting environment more than relationship, but still suggesting space, possibility, and openness.

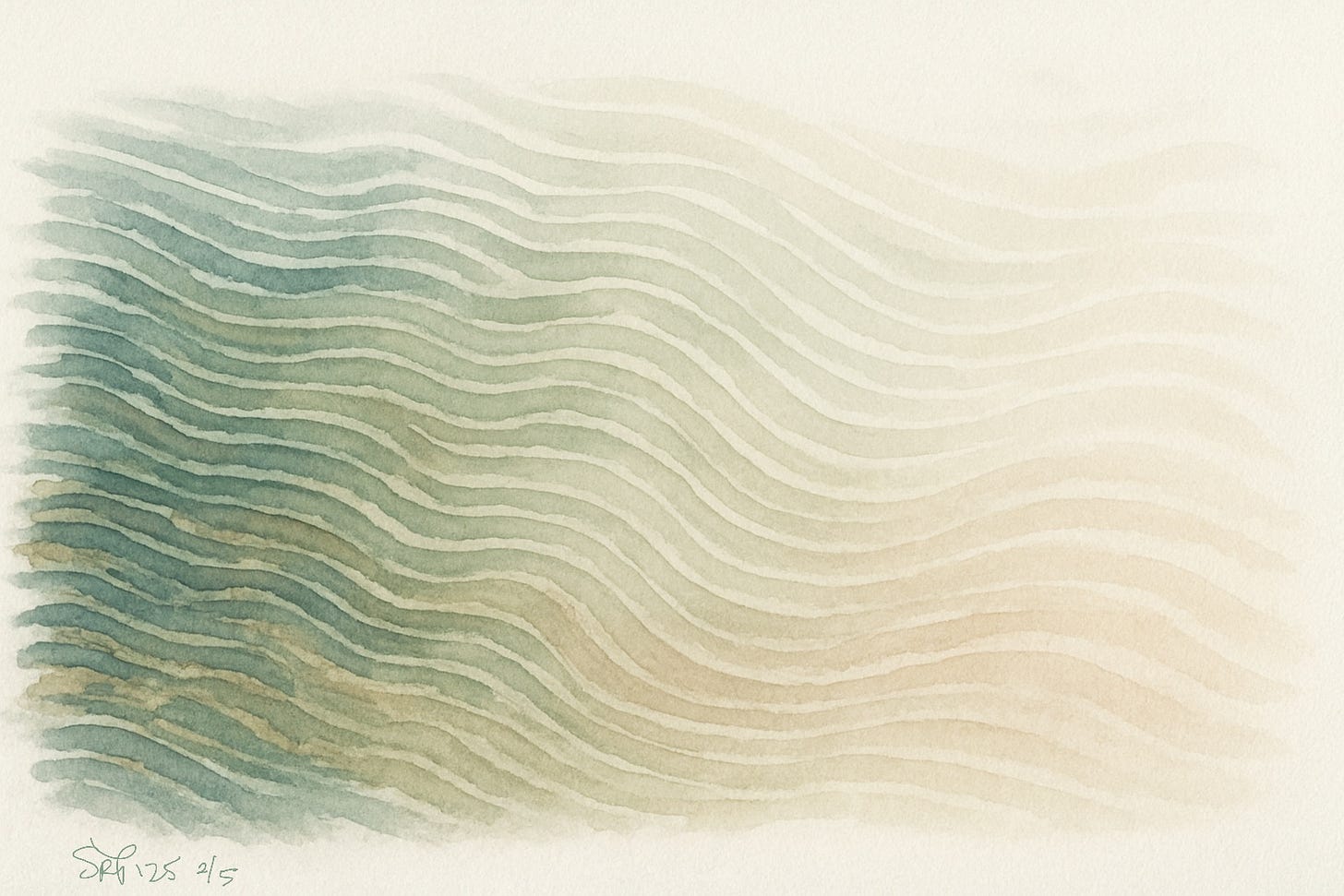

The second piece, my first on paper, introduced individual short strokes in separate breaths, scattered rhythms. I thought about VanGogh’s layered brushwork, making marks to feel distinct and unaligned, representing the patient’s rapid or irregular respiration on top of lighter layers of harp music. Presence begins to emerge in this one. I experimented, getting used to water and pigment, attempting to lay representations of the harp’s steady pulse in lighter hues and the patient’s elevated breath in darker ones. Across the page, I start to work on my blending and layering to hint at a gentle pull toward cohesion.

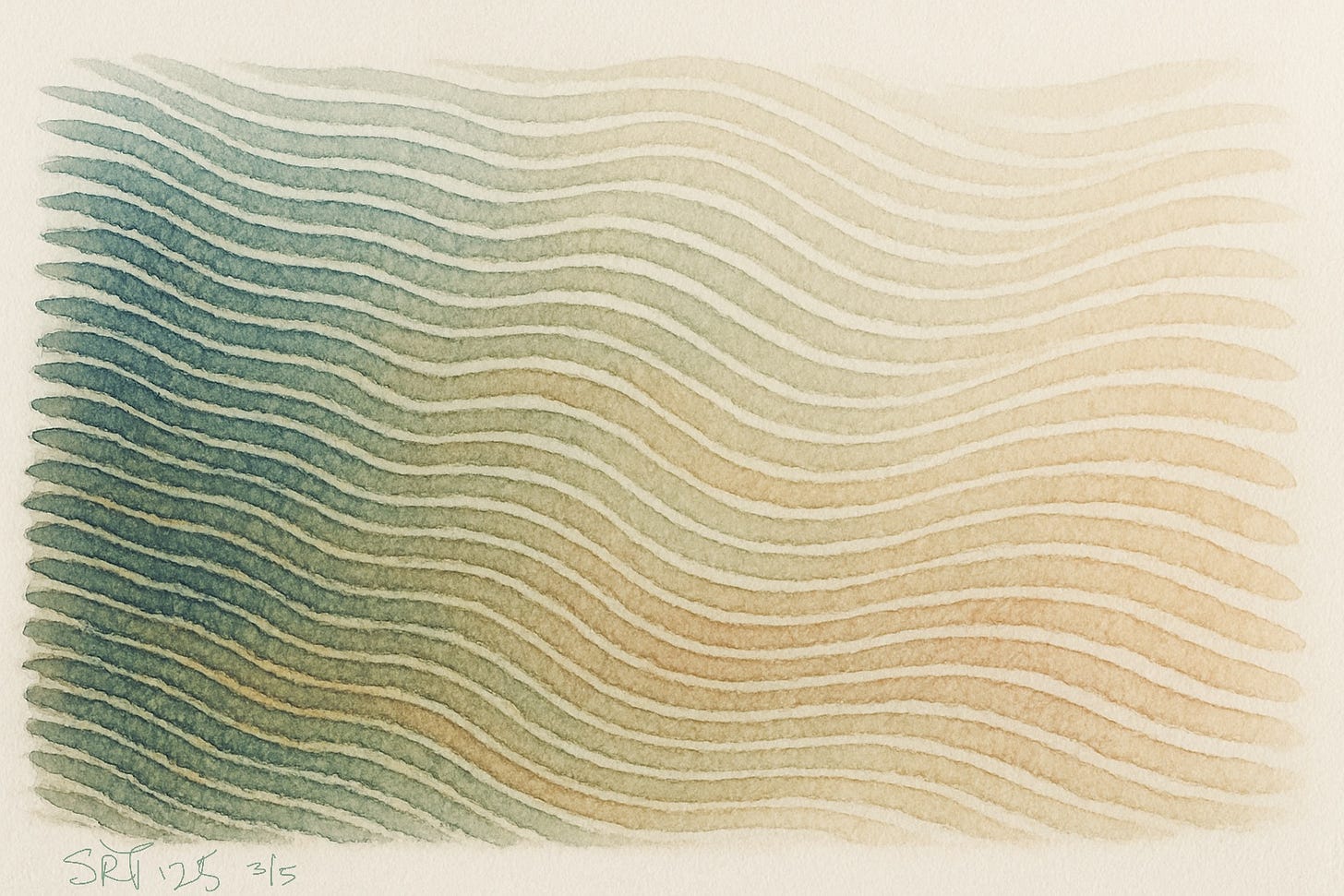

In my third painting, I focused more on color, working with tone to communicate a movement from tension toward spaciousness. I’ve softened the strokes, and shifted tones and hues with more water. This piece feels transitional, like an inhale that begins to slow, or a musician adjusting their touch in response to subtle cues.

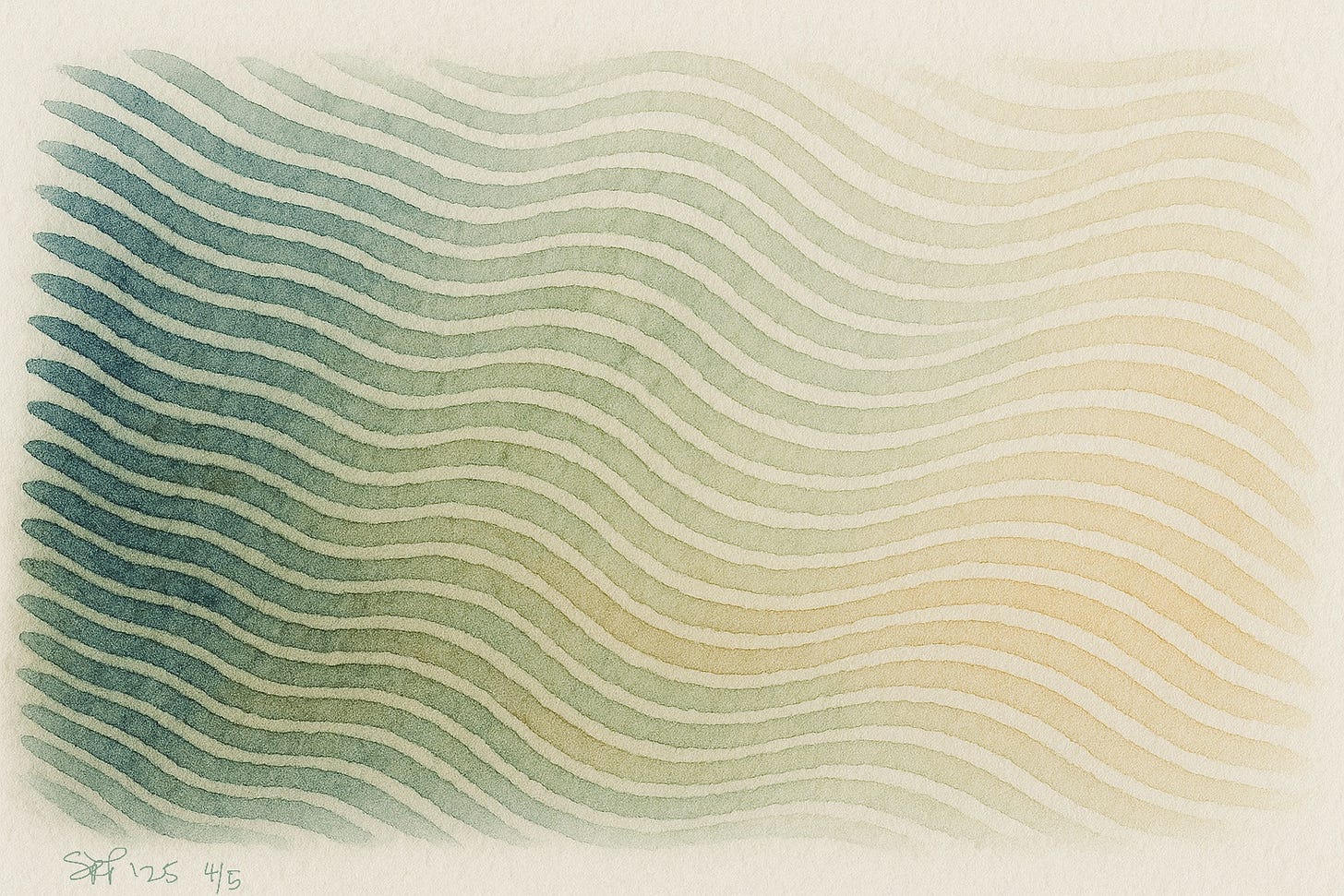

The fourth painting deepens that motion further. I began to lengthen and curve my lines, letting more space open between them. I wanted to invite more air into the composition, more room for each stroke to breathe. The curves stretch wider now, suggesting a steadier inhale, a longer, less hurried exhale.

In this piece, I also began to vary the color more intentionally, introducing subtle shifts and soft tonal contrasts that reflect both consistency and irregularity. Some strokes stand apart, like outliers in a breathing pattern, moments of hesitation or asymmetry. But instead of disrupting the rhythm, they feel authentic. The flow stays intact but seems to be carried by broader movement. This is where I first felt like my painting wasn’t simply showing breath but becoming it.

My last painting was a more direct attempt to use Van Gogh’s language. My strokes remain distinct and textured but move together in a shared motion, to show individual breaths creating a pattern of breathing. I kept my base wash light and translucent to represent the harp’s music as foundational, while the individual breath strokes float on top, shaped but not confined. The pigment brightens and I switched to yellow, perhaps suggesting a movement toward light. Not a dramatic conclusion, but a spacious release.

In Dance Hall in Arles, VanGogh suggests distant figures through tonal contrast and brief gestures instead of detail. There are no outlines, just the sense that someone is there. I tried to echo that using subtle tonal shifts and dispersed strokes to let presence arise from absence. The breath is meant to be felt.

I feel like talking about what I tried to show and how I kept adapting in my paintings, also becomes a metaphor for our work as CTMs. These pieces, like bedside harp, aren’t meant for display. They’re meant to meditate on my feelings about breathing and entrainment, and to attempt to express attunement and presence without insistence. Each brush stroke is meant as a part of a greater system, moving in a kind of companionship — a visual echo of the therapeutic musician’s role at the bedside: listening in color, offering in time.

The Deeper Work

Breath-based tempo isn’t only about slowing the music or decreasing the bpm setting on your metronome.

It’s about entrainment,

when one rhythm begins to align with another,

when one system listens deeply enough to move together.

One rhythm mimics,

then harmonizes,

until they are no longer two separate tempos.

When breath becomes your tempo:

You are no longer leading.

You are no longer following.

You are with.

This is the essence of therapeutic musicianship: attuned, spacious, and deeply embodied listening.